| |

Namibia

schools are on break during May so we didn't have any opportunity to visit a

classroom, but there is a school (left) and clinic (right) in Linyanti so we

took a morning stroll with Emil, a student, to look at the buildings and peek in the windows.

The school has a computer lab. Namibia

schools are on break during May so we didn't have any opportunity to visit a

classroom, but there is a school (left) and clinic (right) in Linyanti so we

took a morning stroll with Emil, a student, to look at the buildings and peek in the windows.

The school has a computer lab.

The

road is paved most of the way to Linyanti. Beyond it is soil, but

generally a very smooth and high quality surface, similar to hard, smooth

composition used in rural America called soil cement. These roads

may not be formulated exactly the same way, but through using the right

clay, wetting, smoothing and packing the road during construction, they seem

to achieve the same results. [The picture of the Lilac Breasted Roller has

absolutely nothing to do with road construction, but they are beautiful

birds and they aren't usually easy to photograph. It is also interesting to

ponder where they perched before man built telephone and power lines across

Africa.] The

road is paved most of the way to Linyanti. Beyond it is soil, but

generally a very smooth and high quality surface, similar to hard, smooth

composition used in rural America called soil cement. These roads

may not be formulated exactly the same way, but through using the right

clay, wetting, smoothing and packing the road during construction, they seem

to achieve the same results. [The picture of the Lilac Breasted Roller has

absolutely nothing to do with road construction, but they are beautiful

birds and they aren't usually easy to photograph. It is also interesting to

ponder where they perched before man built telephone and power lines across

Africa.]

Our

destination for the day was Sangwali. In addition to what was

becoming a pattern of afternoon socializing, we also made the rounds of the

"town." Similar to Linyanti, Sangwali was more of an area than a

center. At one end, on the outskirts, was the police station, down the

road from that was the tribal court (per custom, in the course of the

afternoon we formally presented ourselves to the Headman of the town and the

Chief of Our

destination for the day was Sangwali. In addition to what was

becoming a pattern of afternoon socializing, we also made the rounds of the

"town." Similar to Linyanti, Sangwali was more of an area than a

center. At one end, on the outskirts, was the police station, down the

road from that was the tribal court (per custom, in the course of the

afternoon we formally presented ourselves to the Headman of the town and the

Chief of

Police), further on a few stores were scattered

with several hundred meters between

them, next came a sign-less church, and another walk brought you to the

offices of

the local administration. Beyond that the main road split. One

road lead to the schools and clinic on the opposite outskirts of "town". The other road led to the site

of the future Sheshe Crafts Center, the Sangwali Museum (4 km) and Mamili National

Park (12 km). (The Sheshe Crafts Center used to have a building but now it has been

relegated to a closet in the administration building.) Along the

way people were

carrying things and working at various activities. Police), further on a few stores were scattered

with several hundred meters between

them, next came a sign-less church, and another walk brought you to the

offices of

the local administration. Beyond that the main road split. One

road lead to the schools and clinic on the opposite outskirts of "town". The other road led to the site

of the future Sheshe Crafts Center, the Sangwali Museum (4 km) and Mamili National

Park (12 km). (The Sheshe Crafts Center used to have a building but now it has been

relegated to a closet in the administration building.) Along the

way people were

carrying things and working at various activities.

As we walk around people

did various kinds of work; carrying thatch, pounding sorghum off the stock,

hitching a ride on a sled as the ox team hauled it home, collecting fire wood

and water, fixing a motor, etc.

While access to universal electric power is

still a ways off here (maybe only a few months), there was access to safe drinking water throughout the

town and it seemed that everyone had a cell phone. You could see the

tower with the cell antennas from almost every place in town. As we walk around people

did various kinds of work; carrying thatch, pounding sorghum off the stock,

hitching a ride on a sled as the ox team hauled it home, collecting fire wood

and water, fixing a motor, etc.

While access to universal electric power is

still a ways off here (maybe only a few months), there was access to safe drinking water throughout the

town and it seemed that everyone had a cell phone. You could see the

tower with the cell antennas from almost every place in town.

The

health clinic is a clean and well maintained building. We arrived

during the siesta so it was very quite. One member of our group went

in to have an abrasion dressed (incurred while walking, not bicycling) and was

treated very generously. Other than that we didn't snoop around The

health clinic is a clean and well maintained building. We arrived

during the siesta so it was very quite. One member of our group went

in to have an abrasion dressed (incurred while walking, not bicycling) and was

treated very generously. Other than that we didn't snoop around and

learn anything about local health care and

learn anything about local health care

and health care delivery,

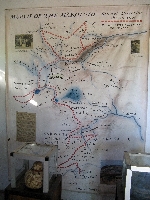

but the walls were informative with posters (several on safe sex and alcohol,

and family planning) (left) and a map of all of the villages in the district, with some

population information (right). and health care delivery,

but the walls were informative with posters (several on safe sex and alcohol,

and family planning) (left) and a map of all of the villages in the district, with some

population information (right).

The

Sangwali Museum is a little big museum.

The one room (one man) museum has informative exhibits on the explorations through the area

by

David Livingston, the plight of

the Helmore missionaries that settled near Sangwali,

the history of the traditional people in the area,

the Makololo, and

information on basketry .

The museum itself is not easy to find and you will need to find the curator

to get in. The curator,

Linus Makwato, is

a treasure

himself with his knowledge of local history,

enthusiasm for his endeavors and generosity to answer questions and share

it all. He has other initiatives and enterprises underway, as

well, to develop the area. The

Sangwali Museum is a little big museum.

The one room (one man) museum has informative exhibits on the explorations through the area

by

David Livingston, the plight of

the Helmore missionaries that settled near Sangwali,

the history of the traditional people in the area,

the Makololo, and

information on basketry .

The museum itself is not easy to find and you will need to find the curator

to get in. The curator,

Linus Makwato, is

a treasure

himself with his knowledge of local history,

enthusiasm for his endeavors and generosity to answer questions and share

it all. He has other initiatives and enterprises underway, as

well, to develop the area.

Road to museum, built by Linus

Road to museum, built by Linus

We passed a lot of the afternoon sitting under a large

tree, meeting and talking to people who came by; school teachers, local

businessmen, farmers, etc.

Accommodations

for the night were on the porch of Ravens and his family. You know your reality

tour to an Africa village is real when the roosters wake you up crowing at 4

AM. That's reality. Get use to it. For the local residence it

is background noise that they have long since gotten used to. For the

visitors, it makes them cranky, but fortunately the tour only lasts

two-weeks and then they can go back home where all they have to deal with

are

the sounds of traffic, emergency vehicle sirens and airplane noise. Accommodations

for the night were on the porch of Ravens and his family. You know your reality

tour to an Africa village is real when the roosters wake you up crowing at 4

AM. That's reality. Get use to it. For the local residence it

is background noise that they have long since gotten used to. For the

visitors, it makes them cranky, but fortunately the tour only lasts

two-weeks and then they can go back home where all they have to deal with

are

the sounds of traffic, emergency vehicle sirens and airplane noise.

As you might have come to expect, there is yet another

language spoken in Sangwali. The dominate ethnic group here is the Mayeyi or Biyeyi who speak Shiyeyi or Maiyeyi: Good morning is "natombuka', good

afternoon is "narashara" and thank you is "takambiri." The

Mayeyi are now known as

the river people, as in the Okavongo River (and tributaries), and the dominate ethnic group in

the northern and eastern sides of the delta. After you get up on dry

land additional ethnic groups are present.

From description in the Sangwali Museum, we learn the following

history:

The Mayeyi are believed to be originally from Congo or north-west Zambia.

The language contains a series of clicks indicating an associate with the

Khoe-khoe. But it is commonly classified as close to Otjiherero (Herero),

and less frequently as close to Sisubiya and Thimbukushu, all Niger-Congo

languages. Culturally, the Mayeyi share many customs with the Mbukushu

and architecture with the Subiya and Mbukushu.

The Mayeyi, after migrating south to the area of the Chobe River and

Linyanti River, end up being pushed further south and west by the Mbukushu

and Masubiya, who were on the move west and south, respectively, in about

1750 to avoid the wrath of the expansionist Lozi. As the Mayeyi moved

southwest, along the west side of the Okavango, they encountered and clashed

with the Herero. Possibly to minimize this conflict the Mayeyi largely

settled along the rivers in the delta. David Livingstone called them river

people. He described the Mayeyi as the 'Quakers of Africa,' because of their

peace-loving nature.

The capital for the Mayeyi of this region is Sangwali. The chieftaincy is

hereditary and can be traced back to before the Lozi (a.k.a. Aluyi) and

Makolo (or Sotho) expansion and control of the area.

The Bamangwato, who are a

branch of the Tswana (named after Ngwato, one

of three sons of Malope who went their separate ways to avoid conflict in

early 1700), lived here for a short time from about

1834. Their chief Moremi, also made his capital where Sangwali now stands,

calling it Tshoroga. They had fled north from Lake Ngami when Sebetoane and

his Makololo reached the area. When the Makololo came to the Sangwali in

about 1838, they ambushed and defeated the Bamangwato and Sebetoane made

it his capital, calling it Linyanti, or Dinyanti. They controled the

region until 1864.

For a while Moremi

continued to live south of here as a subject of Sebetoane, before he

fled back to Lake Ngami with his people. That region is still dominated by

the Bamangwato.

One of the saddest chapters of Sangwali involved the Helmore mission:

(Source Sangwali Museum)

When

David Livingstone departed from

Linyanti in September 1855 to follow the Zambezi to the east coast, he

promised Chief Sekeletu of the Makololo that he would return with his wife

to set up a missionary station amongst them. However, he changed his

plans and the London Missionary Society asked Holloway Helmore to go

instead. Helmore had already been a missionary in southern Africa for 17

years.

In July 1859 Holloway

Helmore with his wife Anne, together with a second missionary Roger Price

and his wife Isabella, set off from Kuruman in the Cape, for the long

journey of approximately 6,000 km through the Kalahari to Linyanti. They

traveled in four ox wagons. The party of 21 people included the four

youngest Helmore children, a Tlhaping teacher, Thabi and some drivers and

herdsmen.

They had a terrible

journey. It was the dry season and most of the water holes had already

dried up. They suffered severely from thirst and the wagons kept breaking

down in the deep, soft sand. The oxen kept wandering away in search of

water. At a water hole in

Letlkane,

Isabella Price gave birth to a baby girl. At one stage, on the Mababe

Plain, for four nights in a row, Helmore walked 30 km to get water for the

stranded party.

Seven months later, on

14 February 1860, they arrived at Linyanti, expecting to meet

Livingstone. He had planned to make his way towards Linyanti from the

east coast, along the Zambezi River. However, he had not yet arrived, nor

had he sent word that he had been delayed. Sekeletu was not happy to

accept Helmore and Price as substitute missionaries. He was still waiting

for Livingstone and his wife to come.

Sekeletu insisted that

the party remain there, in the unhealthy swamps, until Livingstone

arrived. They had made their camp near Sekeletu’s capital, which he also

called Linyanti. This was where Malengalenga is now, about 20 km east of

Sangwali.

It was not long before

all the people in the party fell ill, and the first death occurred in 2

March 1860. Within seven weeks, eight people in the missionary party had

died at Linyanti and were buried there, including Holloway and Anne

Helmore. After Helmore’s death, Roger and Isabella Price decided to

abandon the mission and return to the Cape. Soon afterwards, on the

Mababe Plain, Isabella Price also died. The survivors, Roger Price, the

two orphaned Helmore children and eight helpers eventually arrived back at

Kuruman in February, 1861.

It is still uncertain

as to what caused their deaths. The members of the party had been plagued

by mosquitoes on their journey and most had been ill with fever. It was

not until forty years after these events that scientists discovered that

malaria was carried by mosquitoes.

However, there are

strong grounds for suspecting that Sekeletu had tried to poison them. He

did not welcome this missionary party from the south. He felt that

Livingstone and his wife Mary would be a protection against his enemy the

formidable Mzilikazi, who with his Ndebele people had settled nearby.

Mary Livingstone’s father was the famous missionary Robert Moffat, who was

greatly admired and respected by Mzilikazi.

To this day the local

people say that Sekeletu put poison from the toxic Euphorbia ingens into

the beer that he gave to the party and that he poisoned the oxen he gave

them in the same way. Price also insisted that they had been poisoned.

Perhaps we will never know the true cause of death, but most of those who

died appear to have suffered from fever and poisoning.

In 1864, the Makololo were ambushed in a

surprise raid by the Lozi under Sipopa, one of the sons of their former king, Mulambwa. The Makololo power was completely destroyed. The Lozi then became

rulers. In 1865, they appointed a headman or induna, Kabende

Simata, over the Mayeyi, Mafwe, Mbukushu and Matotela. King Sipopa was succeeded by Lewanika,

who was king from 1884 to 1916.

In the late 19th century, the British South

Africa Company took control of the region, placing it under British

protection, though Lewanika retained the right to rule the people according

to Lozi custom.

In 1909 the German Colonial Administration appointed

the Lozi Kabende Simata Mamili as chief over these people and apart from the

Mayeyi, this situation prevails to the present. Most of the Lozi now live

north of the Zambezi, in Zambia.

|

Addendum:

The

most unique items at the Sheshe Crafts Shop were a couple of piece of woven cloth (see the

border for this section of the website) that initially no one we talked to

seem to know much about.

As I gathered information it seemed to be

conflicting: One explanation was it is from Angola (which probably make it Mbukushu) and is worn by woman during traditional occasions. It is

tied around the waist so that it sits on their buttocks and bounces up and

down when they dance. Later I was told that the cloth has the Siyeyi name "mashamba."

Basketry:

(Source Sangwali Museum)

Basket making among the people of southern Africa is a long-established art

in transition. An art typically handed down from one generation to the next

by the women. There is a standard of form and technique distinctive to each

ethnic group. Inter-tribally variations of design and construction

distinguish the work of one group from that of another.

The people use baskets for storage of liquids or dry

foods, agricultural activities, and transportation of food or fuel. Each of

these functions requires baskets of different shapes and construction.

Both the Bayei and the Hambukushu produce designs

featuring large, geometric patterns which are predominantly asymmetrical.

The Bayei, unlike the Hambukushu, Basotho, and Zulu

weavers, have evolved a series of symbolic patterns which are not confined

to specific families but are shared within the Bayei community. These

patterns, are called by specific names by the weavers. These names all

relate to nature. The Bayei’s constant contact with nature and perception

of animal life provided the stimulus to imitate and express those

observations in an art-form.

Perhaps the most striking design among the Bayei is the

‘Forehead of the Zebra’ (Phatla ya Pitsa). The careful observation

of the zebra with its characteristic pattern of black stripes on a whitish

background has been effectively portrayed in several pieces. The use of

heavy and thin zigzag lines, creating a pattern of movement, fills the

entire space of the containers. Each artisan, by infusing her own ideas and

imagination into the basic design, alters the pattern to some degree.

Another popular design of the region is the ‘Tail of

the Swallow’ (Sentila ya Pelwana).

The deeply curved triangular form

resembling the deeply forked tail of the swallow is arranged in a circular

pattern in the inner section of the basket. The same shape is repeated as an

ornamental border. The addition of curved lines in some of the baskets

gives an illusion of movement like the graceful swift flight of the swallow.

One of the distinct design woven by the Bayei is the

‘Knees of the Tortoise’ (Manole a Khudu), in which bold angular lines

point towards the centers of the baskets. The acute and obtuse angles of

the ‘knees’ represent joints that permit movement.

A design symbolizing an aspect of animal life is the

‘Tears of the Giraffe’ (Dikelede ya

Thutlwa) ‘Long ago the hunters would chase and shoot giraffes.

The giraffe cries before he dies and leaves a trail of tears’, weaver Digang Rasevete explains. The jagged

lines of a typical representation represent the spilt tears of the giraffe.

A simple Bayei design is referred to as ‘Urine of the

Bull’ (Moroto wa Makaba). Here, irregular, wandering lines follow

the contour of the basket in an upward direction to depict the imprinted

trail of the spilt fluid as it is left on the dry desert.

|