Overview of Textiles In Africa

(mostly handmade Africa cloth)

WE WOULD LOVE

YOUR SUPPORT!

Our content is

provided free

as

a public service!

![]() IBF is 100%

IBF is 100%

solar powered

Country Cloth (Liberia, Sierra Leone)

Perhaps the simplest

woven cloth in West Africa is country cloth. Its made in

the interior of Liberia (Lofa County) and in a arc around it which included Ivory Coast,

Burkina Faso, Guinea, Sierra Leone and Mali.

The cotton and skills to weave it probably came into the forest zone with people

migrating from the Sahel

Perhaps the simplest

woven cloth in West Africa is country cloth. Its made in

the interior of Liberia (Lofa County) and in a arc around it which included Ivory Coast,

Burkina Faso, Guinea, Sierra Leone and Mali.

The cotton and skills to weave it probably came into the forest zone with people

migrating from the Sahel

because

of other population pressures, war and famine. Traditionally Liberian country

cloth was handspun, hand dyed and hand woven cotton, done in about four inch wide

strips on a simple foot treadle loom. A standard bolt is about 36 yards

long. The weaving pieces shown to the left are carved heddle pulleys, heddles, batten and reeds, boat and spinning spindles.

because

of other population pressures, war and famine. Traditionally Liberian country

cloth was handspun, hand dyed and hand woven cotton, done in about four inch wide

strips on a simple foot treadle loom. A standard bolt is about 36 yards

long. The weaving pieces shown to the left are carved heddle pulleys, heddles, batten and reeds, boat and spinning spindles.

Often the

cloth was plain white, but

natural dyes like indigo and kola were used to dye the warp to create linear

stripes. The weft was always left natural. To prepare the loom the warp would

be set-up on sticks in the yard of the house. When

the long strip is finished it is cut into

Often the

cloth was plain white, but

natural dyes like indigo and kola were used to dye the warp to create linear

stripes. The weft was always left natural. To prepare the loom the warp would

be set-up on sticks in the yard of the house. When

the long strip is finished it is cut into

pieces of the desired length which are

then sewn together a piece of cloth.

Traditionally clothing was made without much tailoring. A piece of cloth

with enough strips to achieve the desired width would be

pieces of the desired length which are

then sewn together a piece of cloth.

Traditionally clothing was made without much tailoring. A piece of cloth

with enough strips to achieve the desired width would be partially sewn together

on the sides and an opening for the head would be cut and sewn off. The neck and

pocket are often embroidered. This also serves to strengthen these stress

areas.

partially sewn together

on the sides and an opening for the head would be cut and sewn off. The neck and

pocket are often embroidered. This also serves to strengthen these stress

areas.

Further north and east similar cloth was woven on similar looms, but the strips were generally wider.

Dogon

Cloth (Mali, Burkina Faso)

Dogon

Cloth (Mali, Burkina Faso)

The Dogon people of Mali make a similar cloth from narrow cloth but it usually is woven all natural, certainly the warp is not died. They do some weaving with died waft, usually to create a border stripe near the ends in pieces intended to be used as shawls or blankets.

The traditional Dogon boy's shirt is all natural, has a narrow v-neck and is

often decorated with tassels. Men's shirts tend white, indigo or brown and

don't have the tassels. If the shirt was for hunting it would likely be

brown and decorated with amulets, horns and other traditional medicine to help

improve the hunter's

The traditional Dogon boy's shirt is all natural, has a narrow v-neck and is

often decorated with tassels. Men's shirts tend white, indigo or brown and

don't have the tassels. If the shirt was for hunting it would likely be

brown and decorated with amulets, horns and other traditional medicine to help

improve the hunter's effectiveness (i.e. make him stealth.)

effectiveness (i.e. make him stealth.)

In the case of the checked Dogon blanket to the left the weaver diverged from a

couple of traditional practices: He alternated between sections with white

waft and black waft to create a checker board look. He also used

industrially manufactured tread, which made it easier to have consistent sized

patches.

checker board look. He also used

industrially manufactured tread, which made it easier to have consistent sized

patches.

Click here for a virtual tour of to Dogon Country, Mali.

Indigo Cloth (West Africa)

For

solid colored cloth, traditional weavers weave and sew a natural colored

cloth (off-white) and then dye the whole piece. There are a number of traditional

vegetable and mineral based natural dyes available. A favorite color,

especially among women, is indigo blue. For the Dogon, the dying process is often combined with

tying the cloth to get a stippled look. These are often worn as

wrap-around skirts.

For

solid colored cloth, traditional weavers weave and sew a natural colored

cloth (off-white) and then dye the whole piece. There are a number of traditional

vegetable and mineral based natural dyes available. A favorite color,

especially among women, is indigo blue. For the Dogon, the dying process is often combined with

tying the cloth to get a stippled look. These are often worn as

wrap-around skirts.

Additional indigo cloth comes from Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Mali. The dark blue color is derived from the dye of the indigo plant. The plant has pinnate leaves and clusters of red or purple flowers that are used to produce the dye indigo. A good 4’x6’ piece can sell for $50

Kente Cloth (Ghana, Togo)

The

most revered hand-woven narrow strip cloth is Ashanti Kente. It is

considered a prestige item because of the time and skill it takes to weave.

It is woven by the Ashanti (or Asante) people of southern Ghana. It is the cloths

of the King and court of the Ashanti empire and is now used for distinguished events

around the

African continent and in the Diaspora. Kente cloth seem to imbue power in any

location.

The

most revered hand-woven narrow strip cloth is Ashanti Kente. It is

considered a prestige item because of the time and skill it takes to weave.

It is woven by the Ashanti (or Asante) people of southern Ghana. It is the cloths

of the King and court of the Ashanti empire and is now used for distinguished events

around the

African continent and in the Diaspora. Kente cloth seem to imbue power in any

location.

Kente cloth originated from the Fante people of Ghana, who sold this fabric in baskets. The Fante word for basket is “kenten”. Authentic Kente cloth is typically woven in 4-inch wide strips. A full size piece of Kente is about 3 meters by 4 meters. The designs may be symbolic representations of historic events, have religious, political, and even financial significance, or be purely geometric. Today, there’s a pattern to indicate the importance of almost any special occasion, and colors are chosen to reflect customs and beliefs: Red represents death or bloodshed, and is often worn during political rallies; green stands for fertility and vitality, and is worn by girls during puberty rites; white means purity or victory; yellow represents glory and maturity and is worn by chiefs; gold, for continuous life, is also worn by chiefs; blue, for love, is often worn by the queen mother; and black, meaning aging and maturity, is used to signify spirituality. Because of its vibrant beauty and regal legacy as a cloth fit for kings and queens, authentic Kente remains one of the most popular Africa fabrics. Generally the high the percentage of the cloth that is intricately woven the more valuable the piece. All other things being equal, Kente made with silk thread is more expensive than that made with cotton thread. A good full size piece can sell for from $500 to $2000.

A second Kente is Ewe Kente, which tends to be cotton, simpler patterns and not as brightly colored. The Ewe people live in southeast Ghana and southwest Togo.

A third similar cloth is hand-woven Ashokie Cloth from Ghana and Nigeria, West Africa. The Yoruba in Nigeria reserved this cloth for funerals, religious rituals, and other formal occasions.

Djerma Cloth and Hausa Cloth (Niger, Nigeria)

Djerma

Cloth and Hausa Cloth are made from four to eight inch wide strips.

It is most commonly made with manufactured thread. They are similar to each other and which is which may be

disputed. In that they are strip-cloth they are similar to Kente, but woven on

a wider loom and not done in silk or rayon. In my experience Djema uses

narrower strips and is the more

colorful and intricate of the two.

Djerma

Cloth and Hausa Cloth are made from four to eight inch wide strips.

It is most commonly made with manufactured thread. They are similar to each other and which is which may be

disputed. In that they are strip-cloth they are similar to Kente, but woven on

a wider loom and not done in silk or rayon. In my experience Djema uses

narrower strips and is the more

colorful and intricate of the two.

Khasa or Fulani Blankets (Mali)

Khasa

or Fulani Blankets

consists of heavy woolen striped blankets that are woven by the Fulani of Mali.

The textile is typically 6 to 8 feet long and woven in 8-inch wide strips.

Although the traditional blanket is white, it is also common to have yellow,

black, or red strips. Khasa were used by the semi nomadic Fulani during the cold season.

Traditionally women would hand spin and dye the wool and men would weave the

blankets. Patterns included in the design are lines, spots, triangles, lozenges

and chevrons which depict Fulani myths and pastoral life symbolically.

Newer blankets tend not to have the fineness and quality of older blankets.

Click here for a virtual tour of Mali.

Khasa

or Fulani Blankets

consists of heavy woolen striped blankets that are woven by the Fulani of Mali.

The textile is typically 6 to 8 feet long and woven in 8-inch wide strips.

Although the traditional blanket is white, it is also common to have yellow,

black, or red strips. Khasa were used by the semi nomadic Fulani during the cold season.

Traditionally women would hand spin and dye the wool and men would weave the

blankets. Patterns included in the design are lines, spots, triangles, lozenges

and chevrons which depict Fulani myths and pastoral life symbolically.

Newer blankets tend not to have the fineness and quality of older blankets.

Click here for a virtual tour of Mali.

Bogolanfini or Mud Cloth (Mali)

There

are several mud

cloth in West Africa. The most prominent is said to have originated

with the women of Mali where it is called Bogolan cloth or Bogolanfini

(a composite of bogo, meaning "earth" or "mud"; lan, meaning

"with" or "by means of"; and fini, meaning "cloth".) One center of

high quality Bogolanfini production is the town of San, so it is

sometimes referred to as San Cloth.

There

are several mud

cloth in West Africa. The most prominent is said to have originated

with the women of Mali where it is called Bogolan cloth or Bogolanfini

(a composite of bogo, meaning "earth" or "mud"; lan, meaning

"with" or "by means of"; and fini, meaning "cloth".) One center of

high quality Bogolanfini production is the town of San, so it is

sometimes referred to as San Cloth.

Traditionally, Bambara (Bamanan) women, as well as those of the Minianka, Senufo, Dogon, and other ethnic groups, produced the cloth for important life events and taught the process to their daughters. Men, especially hunters, wore it for hunts and celebrations. Today, both women and men make mud cloth for sale in markets, and Malian students study it at the arts academy.

Mud cloth is made from narrow strips of handspun and hand woven cottons, which are sewn together in various widths and lengths. The cloth is first dyed with a yellow solution. Different sources have this as "a dye bath made from mashed and boiled, or soaked, leaves of the n'gallama tree (Anogeissus leiocarpus)," "an extracted from the bark of the M'Peku (Lannea velutina) tree and the leaves and stems of the Wolo tree," "a brown solution made from pounded Bougalan tree leaves and other ingredients made by specialists," or "a special solution of pounded leaves from the Bogolon tree." Parsing the information the first description might be the traditional method, the second description is part a short cut that has been developed but which produces lower quality prints, and the third and forth descriptions use variation of bogolan, which we are told translates as "mud."

The

solution acts as a mordant or fixative. Then using carved bamboo or wooden

sticks, symbolic designs are applied in mud that has been collected from

riverbanks and allowed to ferment over time in clay pots. After the mud is

applied to the cloth, it is dried in the sun and washed. The process is repeated

several times to obtain a rich color that is deeply imbued in the cloth. When it

reaches the desired hue, the cloth is washed with a caustic solution to remove

debris and to brighten the background. Today, mud cloth come in background

shades of white, yellow, rich brown, light brown, gold, and rust. A good

traditional 4’x6’ piece can sell for $50.

The

solution acts as a mordant or fixative. Then using carved bamboo or wooden

sticks, symbolic designs are applied in mud that has been collected from

riverbanks and allowed to ferment over time in clay pots. After the mud is

applied to the cloth, it is dried in the sun and washed. The process is repeated

several times to obtain a rich color that is deeply imbued in the cloth. When it

reaches the desired hue, the cloth is washed with a caustic solution to remove

debris and to brighten the background. Today, mud cloth come in background

shades of white, yellow, rich brown, light brown, gold, and rust. A good

traditional 4’x6’ piece can sell for $50.

Click here for a virtual tour of Mali.

Korhogo Cloth (Ivory Coast)

Another

version of 'mud cloth' is Korhogo cloth or dung cloth or 'a slang word

for dung' cloth -- which is purported to used in the tincture and give the cloth

a slight odor before it dries. Korhogo cloth is made by the Senufo people

in and around Korhogo, Ivory

Coast. They start with natural colored handspun and hand woven strips that are

about five-inch. These are cut to the desired length and sewn together. Mud is painted on the cloth

to create patterns of animals, men in ceremonial dress, buildings, or geometric

designs. The soil used to make this mud is usually black, brown, or rust and is

collected throughout West Africa.

Korhogo cloth

comes in various lengths

and widths. A good 4’x6’ piece can sell for $50.

Another

version of 'mud cloth' is Korhogo cloth or dung cloth or 'a slang word

for dung' cloth -- which is purported to used in the tincture and give the cloth

a slight odor before it dries. Korhogo cloth is made by the Senufo people

in and around Korhogo, Ivory

Coast. They start with natural colored handspun and hand woven strips that are

about five-inch. These are cut to the desired length and sewn together. Mud is painted on the cloth

to create patterns of animals, men in ceremonial dress, buildings, or geometric

designs. The soil used to make this mud is usually black, brown, or rust and is

collected throughout West Africa.

Korhogo cloth

comes in various lengths

and widths. A good 4’x6’ piece can sell for $50.

Tie Dye Cloth (West Africa)

Tie

dye fabric is popular in Africa. A common method of tie dyeing is the formation

of patterns of large and small circles in various combinations. This is found

particularly among people from Senegal to Nigeria (Gambia, Mali, Burkina Faso,

Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo and Benin.) There are several techniques used

for resist-dyeing. For instance, a cloth is tied or stitched tightly so that

the tying or stitching prevents the dye from penetrating the fabric, and

sometimes-starchy substance is applied to the textile. This will resist the dye

giving pale areas on a dark background when it’s washed at the end of the dyeing

process. Another method of tie dyeing consists

Tie

dye fabric is popular in Africa. A common method of tie dyeing is the formation

of patterns of large and small circles in various combinations. This is found

particularly among people from Senegal to Nigeria (Gambia, Mali, Burkina Faso,

Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo and Benin.) There are several techniques used

for resist-dyeing. For instance, a cloth is tied or stitched tightly so that

the tying or stitching prevents the dye from penetrating the fabric, and

sometimes-starchy substance is applied to the textile. This will resist the dye

giving pale areas on a dark background when it’s washed at the end of the dyeing

process. Another method of tie dyeing consists

of folding a strip of cloth into

several narrow pleats and binding them together. The folds and the binding

resist the dye to produce a linear and cross-hatched effect. Another very popular tie-dyeing

technique is to paint freehand with starch before dyeing in

order to resist the dye. These are only a few examples of tie-dyeing methods

used in Africa today. The tie dye process is time-consuming, but it

increases the diversity of patterns and offers the artist control over the

finished product. In Africa, tie dyeing is approached with care and creativity.

of folding a strip of cloth into

several narrow pleats and binding them together. The folds and the binding

resist the dye to produce a linear and cross-hatched effect. Another very popular tie-dyeing

technique is to paint freehand with starch before dyeing in

order to resist the dye. These are only a few examples of tie-dyeing methods

used in Africa today. The tie dye process is time-consuming, but it

increases the diversity of patterns and offers the artist control over the

finished product. In Africa, tie dyeing is approached with care and creativity.

Another

element is the artistry of tie-dye is the choice of fabric. Higher quality

pieces often use a "brocade" cloth which has additional texture because a

pattern of geometrics or floral design has been woven into the cloth (click on

the two examples here.) Authentic African brocade fabric, also called basin fabric,

can sell for about $12 for a four by five foot piece.

Another

element is the artistry of tie-dye is the choice of fabric. Higher quality

pieces often use a "brocade" cloth which has additional texture because a

pattern of geometrics or floral design has been woven into the cloth (click on

the two examples here.) Authentic African brocade fabric, also called basin fabric,

can sell for about $12 for a four by five foot piece.

There are hundreds of uses for tie dye cloth (bedding, bundle cloths, table cloths, curtains, etc) but one of the primary uses is for clothing.

Batik Cloth

Batik

is a Javanese work but the technique existed in Egypt in the 4th century BCE,

likely long before there was direct cultural communications between Egypt and

Indonesia. Batik has a long history in Africa as well but the details are fuzzy.

It is not unreasonable to infer that moved along trade route 1000 years ago.

It is now well established in East and West Africa, if nothing else as a

contemporary art form.

Batik

is a Javanese work but the technique existed in Egypt in the 4th century BCE,

likely long before there was direct cultural communications between Egypt and

Indonesia. Batik has a long history in Africa as well but the details are fuzzy.

It is not unreasonable to infer that moved along trade route 1000 years ago.

It is now well established in East and West Africa, if nothing else as a

contemporary art form.

By

the 1960's it had almost died out as a craft in Burkina Faso (then Upper Volta)

and was reintroduced by a Peace Corps Volunteer looking for possible income

generating projects. It has continued to evolve since then. The early

pieces were done on thick, heavy handmade strip cloth. New works are being

done on thinner industrial cotton fabric.

looking for possible income

generating projects. It has continued to evolve since then. The early

pieces were done on thick, heavy handmade strip cloth. New works are being

done on thinner industrial cotton fabric.

Traditionally,

batik

is a manual wax-resist process. A wax design is stamped, brushed or combed onto the

fabric and allowed to dry or harden. The cloth is then immersed in dye.

The pieces of fiber that are encased in wax keep the underlying color and the

unprotected fabric takes on the new color. To produce a multicolor

effect, colors are applied one top of the other, beginning with the lightest

color. For instance, a cloth is dyed yellow, and then melted wax is applied to

areas that are yellow. The cloth is dried after each stage of the dyeing

process. A complex piece can take months to complete. At the end the wax is removed by scraping or boiling it off the cloth.

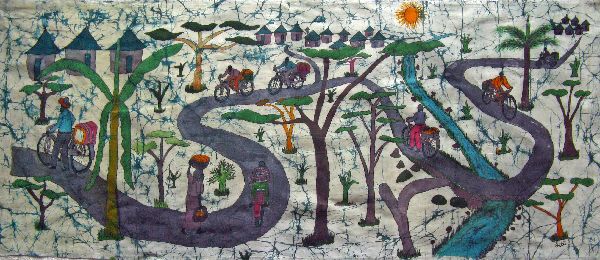

The four pieces below are: Women preparing food (Burkina Faso), woman pounding

grain (Burkina Faso), Mende helmet mask (Liberia), and a bicyclist leaving a

village (Kenya).

dry or harden. The cloth is then immersed in dye.

The pieces of fiber that are encased in wax keep the underlying color and the

unprotected fabric takes on the new color. To produce a multicolor

effect, colors are applied one top of the other, beginning with the lightest

color. For instance, a cloth is dyed yellow, and then melted wax is applied to

areas that are yellow. The cloth is dried after each stage of the dyeing

process. A complex piece can take months to complete. At the end the wax is removed by scraping or boiling it off the cloth.

The four pieces below are: Women preparing food (Burkina Faso), woman pounding

grain (Burkina Faso), Mende helmet mask (Liberia), and a bicyclist leaving a

village (Kenya).

Print Cloth

African

print fabrics come from a batik tradition and were imported from Indonesia

starting in the colonial period. On some piece there are still tags that

reference "wax-resist" and/or "Java." Depending upon where you are on the

continent this cloth can be referred to as lappa (Liberia, Sierra Leone), wrappa,

pagne (Francophone West Africa), kanga (East Africa)

African

print fabrics come from a batik tradition and were imported from Indonesia

starting in the colonial period. On some piece there are still tags that

reference "wax-resist" and/or "Java." Depending upon where you are on the

continent this cloth can be referred to as lappa (Liberia, Sierra Leone), wrappa,

pagne (Francophone West Africa), kanga (East Africa)

[Kikois, shukas, gabis and netellas are East African woven cloths, discussed below.]

Most of this cloth is now machine

made and printed. They are used for

Most of this cloth is now machine

made and printed. They are used for hundreds of purpose (clothing, bedding,

bundle cloths, mops, table cloths, sun shades, curtains, etc) and can and do

endure heavy wear and tear. Much of the fabrication is now done in Africa. At any given

time there can be hundreds of designs in a big urban market. The designs change

from region to region. In West Africa the designs are likely to be repetitive

prints and East Africa cloth often includes a proverb. (The saying on the

red cloth, "Mama nipe radhi kuishi na watu kazi" is about mothers giving for people to live.)

hundreds of purpose (clothing, bedding,

bundle cloths, mops, table cloths, sun shades, curtains, etc) and can and do

endure heavy wear and tear. Much of the fabrication is now done in Africa. At any given

time there can be hundreds of designs in a big urban market. The designs change

from region to region. In West Africa the designs are likely to be repetitive

prints and East Africa cloth often includes a proverb. (The saying on the

red cloth, "Mama nipe radhi kuishi na watu kazi" is about mothers giving for people to live.)

In a years time there can be nearly a

complete turnover in the patterns and color combinations available in the market. Some

prints commemorate events and have an even shorter shelf life. (This cloth

commemorates Barak Obama's election to President of the United States. The

caption translates, "God has given us love and peace.")

In a years time there can be nearly a

complete turnover in the patterns and color combinations available in the market. Some

prints commemorate events and have an even shorter shelf life. (This cloth

commemorates Barak Obama's election to President of the United States. The

caption translates, "God has given us love and peace.")

A two-meter piece will sell for from is $8 to $30, depending upon the weight and quality of the cloth and dyes.

Adinkra Cloth (Ghana)

Adinkra cloth is made by embroidering together six

wide long panels of dyed cotton. The full size can be 3 yards by 4 yards. The

panels are stamped with symbols carved into calabash. The

natural dye is made from the bark of the "badie" tree, which is heated with iron

slag for 3 to 5 days until is thick black goo. Adinkra patterns are

numerous, ranging from crescents to abstracts forms; each of the symbols

carries it own significance and represents events of daily life activities.

As stated in “The Spirit of African Design”, Adinkra means “farewell” and was

used for funerals and to bid a formal farewell to guests. Dark colors, like

brick red, brown, or black, were associated with death while white, yellow, and

light blue were worn for festive occasions. The cloth is still produced in Ghana

today, but now a days you can find the symbols all over west Africa on walls,

furniture, house wares, graphics, etc. Below are charts (four sections)

that explain some of the Adinkra symbols.

Adinkra cloth is made by embroidering together six

wide long panels of dyed cotton. The full size can be 3 yards by 4 yards. The

panels are stamped with symbols carved into calabash. The

natural dye is made from the bark of the "badie" tree, which is heated with iron

slag for 3 to 5 days until is thick black goo. Adinkra patterns are

numerous, ranging from crescents to abstracts forms; each of the symbols

carries it own significance and represents events of daily life activities.

As stated in “The Spirit of African Design”, Adinkra means “farewell” and was

used for funerals and to bid a formal farewell to guests. Dark colors, like

brick red, brown, or black, were associated with death while white, yellow, and

light blue were worn for festive occasions. The cloth is still produced in Ghana

today, but now a days you can find the symbols all over west Africa on walls,

furniture, house wares, graphics, etc. Below are charts (four sections)

that explain some of the Adinkra symbols.

Abomey Appliqué (Benin)

The

art of Abomey appliqué was developed during the Dahomey Kingdom (now in the West

African country of Benin), from 1600 to 1900. Throughout its history each Fon (king) had special symbols and proverbs associated

with his rule. The symbols were used to decorate wall hangings, flags,

umbrellas, buildings and other royal

The

art of Abomey appliqué was developed during the Dahomey Kingdom (now in the West

African country of Benin), from 1600 to 1900. Throughout its history each Fon (king) had special symbols and proverbs associated

with his rule. The symbols were used to decorate wall hangings, flags,

umbrellas, buildings and other royal items during the rein of the king.

The making of appliqués has now become a craft and traditional and

non-traditional designs are available. In additional to traditional themes

there are now appliqué pieces with maps of Africa, wild animals

themes, and village scenes.

items during the rein of the king.

The making of appliqués has now become a craft and traditional and

non-traditional designs are available. In additional to traditional themes

there are now appliqué pieces with maps of Africa, wild animals

themes, and village scenes.![]() They can be found in the markets in Benin, and

tourist markets in the capital cities of adjacent countries.

They can be found in the markets in Benin, and

tourist markets in the capital cities of adjacent countries.

The

royal symbols and other motifs are also being incorporated into woven strip

cloth that can be used as runners, placemats, pillow covers or on other similar

craft projects.

The

royal symbols and other motifs are also being incorporated into woven strip

cloth that can be used as runners, placemats, pillow covers or on other similar

craft projects.![]()

Click here for more information on Abomey and the Dahomey Kingdom.

More on Africa

Bibliography for Africa: Delve more into the literature, culture, history, philosophy and science of Africa.

General

Country-by

-Country Travel

Resources:

Algeria

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Cameroon

Cote d'Ivoire

Dem. Rep of Congo

Djibouti

Egypt

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Kenya

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Morocco

Mozambique

Niger

Nigeria

Senegal

Sierra Leone

Sudan

Somalia

South Africa

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Zaire

Zambia

Zimbabwe

For current news on Africa and more web sites with country-by-country information go to the link section and click on "Africa: News, Background, Travel."

Home | About Us | Contact Us | Contributions | Economics | Education | Encouragement | Engineering | Environment | Bibliography | Essay Contest | Ibike Tours | Library | Links | Site Map | Search

![]()

The International Bicycle Fund is an independent, non-profit organization. Its primary purpose is to promote bicycle transportation. Most IBF projects and activities fall into one of four categories: planning and engineering, safety education, economic development assistance and promoting international understanding. IBF's objective is to create a sustainable, people-friendly environment by creating opportunities of the highest practicable quality for bicycle transportation. IBF is funded by private donation. Contributions are always welcome and are U.S. tax-deductible to the extent allowed by law.

![]()

![]() Please write if you have questions, comment, criticism, praise or

additional information for us, to report bad links, or if you would like to be

added to IBF's mailing list. (Also let us know how you found this site.)

Please write if you have questions, comment, criticism, praise or

additional information for us, to report bad links, or if you would like to be

added to IBF's mailing list. (Also let us know how you found this site.)