Transport And Society

WE WOULD LOVE

YOUR SUPPORT!

Our content is

provided free

as

a public service!

![]() IBF is 100%

IBF is 100%

solar powered

![]()

Bicycle Messengers and

Activism in San Francisco

By Nicholas Wright (2003)

Who are Messengers?

They might take the job because they love to ride, but many bicycle messengers are also at the forefront of urban bicycle activism. It is hard to say one thing about all “messengers,” as they call themselves; they are a unique and varied breed. Poorly understood by the mainstream, this group has their own music, magazines, advocacy organizations, and culture. They are a smart, political and creative band of free-thinkers. They work an extremely dangerous job, and working conditions are poor—long hours, low wages and few or no benefits. No standards regulate this industry save the federal minimum wage. In San Francisco, messengers can sometimes work 11 hours for 80 dollars in weather from icy fog to intense reflected sun and drenching rain. A stark reflection of their substandard conditions and wages, labor activism among rank-and-file bike messengers has swelled and ebbed for decades in America’s urban hubs, both with and without official union backing.

Activist Messengers in S.F.

San Francisco is a bike messenger Mecca with its incredible hills, narrow alleys and booming financial districts. It is also home to many premier examples of messenger activism. Messengers there have united into groups that press for more car-free streets and better bicycle paths. Bicycle messengers constitute a legitimate political force in the city, and the Board of Supervisors has officially declared October 9th as Bicycle Messenger Appreciation Day. In a town with one pedestrian or cyclist fatality a week, they fight for safer streets and higher fines for running reds, and educate drivers and urban cyclists alike about sharing the road. San Francisco messengers boast the world’s first Courier Disaster Response Team; a group of volunteer messengers trained in rescue, first aid, and disaster response. They know the streets and alleys like no others, and in the event of urban cataclysm they will administer rescue and first aid in places ambulances cannot access. Together with groups like the San Francisco Bike Coalition, the San Francisco Bike Messenger Association (SFBMA) advocates for a bike friendly city.

S.F. Courier Industry History

Same-day courier services have a long history in San Francisco; there is some irony that a railway strike in 1894, which halted mail delivery in the Bay area, spawned an industry that expanded for a hundred years. For many decades it was a modest job, just another integral part of city life. With the influx of young people from all over the country in the sixties, the job changed as it became largely performed by people who were not native to town and often simply passing through. Towards the end of the seventies and the into eighties, “messengering” gained its now notorious reputation for wild and rebellious employees that seemed a little weird to most of the people who paid to have their packages delivered by them. The first all-bicycle messenger company was founded in 1945, and survived in the city until a larger company swallowed it up in 1998. For almost sixty years, courier companies of varying sizes have come, gone, and hung on in San Francisco. However, events at end of the century changed the face of courier companies, and the way bicycle messengers organize for change.

The Frisco Dot-Com Boom and Bust

San Francisco was the epicenter of the dot-com boom and bust. An unprecedented era of economic prosperity graced the financial districts. The same boom cursed working class neighborhoods as landlords evicted long time residents en masse so that their old rent controlled apartments could be converted to live/work lofts.

The commerce of the internet revolution initially put San Francisco courier companies into overdrive, as business levels tripled. Although expanding big business was dependent on bike, vehicle, and walking messengers, those who delivered the papers and packages shared little in the spoils of the boom—their real wages stayed steady or, in some cases, decreased. Several messengers in the late 1990s formed their own companies to counteract lousy conditions in the industry, and company owners “with their bike seats still warm” offered higher pay and expanded benefits to cycling and walking messengers.

As the dot-com bubble burst and the new internet based enterprises began to drop like flies, the city saw an accelerating wave of consolidation in all industries. The same-day courier service was no exception. Although a few progressive messenger companies survived and a few more have begun to rise out of the city’s economic rubble, courier services like these were some of the first casualties when the dot-com gold rush began to sour from the top down. Small companies went belly-up, and those that did not were purchased by bigger fish.

In 1998, global players Dispatch Management Services (DMS) Corporation bought up nine small independent messenger companies in San Francisco, and three years later consolidated all their holdings in the city into one name, City-Sprint Corporation.

As business levels and wages plummeted, while rents hung on at inflated rates, bike messengers had more impetus than ever to attempt to bargain collectively with their employers to try to improve conditions. Now they often found themselves dealing not with a local business owner or former messenger, but with transnational companies with operations in dozens of cities worldwide, like CitySprint/DMS. As business levels off, today’s competition among courier companies is as fierce as ever. At times, messenger activism has been fierce enough to combat it.

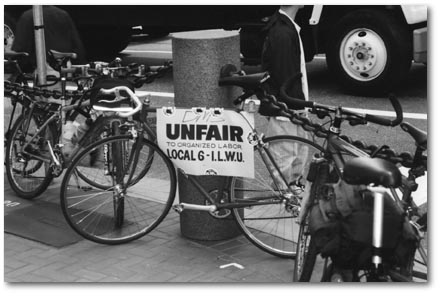

In 1998 the SFBMA reached a landmark agreement with International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) Local 6, where the ILWU gave the messenger administrative, tactical, and financial support.

Eventually, several San Francisco courier companies, including Speedway and Professional Messenger, signed union contracts. The contracts include increased payouts, somewhat better benefits, legal holiday and vacation pay, and abolish a daily fee for vehicle drivers to use company cars. These agreements, and a general improvement in the city’s messenger working conditions, came about in part due to two wildcat strikes organized solely by messengers; one at DMS in January 2000, and another at Flash Messenger in January 2001.

The DMS and Flash Strikes

The five-day wildcat strike at DMS was the longest messenger strike in the city’s history. On January 12, 2000 all 38 bicycle messengers, one clerical worker and several drivers struck, independently of any union. After the strikers shut down business for a working week they earned a 60% raise and rainy day and winter bonuses. Retroactive pay was returned to DMS messengers who had had money illegally deducted from their paychecks. Throughout San Francisco the industry saw a rise in wages after the strike. As the messengers themselves put it, “It didn’t happen by asking politely.” When DMS messengers did sign official union recognition cards with the ILWU a year later, the company closed its doors permanently and without warning. The strike at Flash the next year was not as successful, but both direct actions made front-page news. The city’s messengers are still involved in a struggle for their rights as workers.

Unfortunately, none of the original contracts have been renewed, leaving many messengers disappointed and disillusioned with the ILWU. They feel that standard union tactics smother their own power and funnel it into slow and biased courts. Their wildcat strikes and worker solidarity, they hold, are much more effective techniques.

The Archives

The events of both strikes are documented in the invaluable records kept by one principle strike organizer. Strikers used art and the printed word to generate sympathy and support for their cause. The messenger subculture is full of expressive and imaginative artists, and the posters, fliers, and magazines they created are pointed, often hilarious, and always in the distinct style of the San Francisco bike messengers who created them. As well as for their visual and historical value, they illustrate the classic labor dispute between the often radical messengers and the slightly more conservative ILWU. The records are highlighted by these items but they also include news clippings, photographs, meeting minutes and correspondence. They have recently been organized and are now housed at the San Francisco Labor Archives and Research Center. This collection is divided into three series. The first series consists of records produced and compiled in relation to the messenger strike at CitySprint-DMS in January 2000. The second series consists of records produced and compiled in relation to the messenger strike at Flash Messenger Service in January 2001. The third series consists of other courier and bicycle messenger related material pertaining to organized labor and collection action, complied by the donor. They join the record of the city’s rich labor history, where they can be used and learned from by researchers, students, organizers and the messengers themselves. IBF provided a grant for the preparation of this collection.

Messenger activism, unionization, and labor actions have also occurred in Portland, London, Buenos Aires, and New York, to name a few. There are messenger operated organizations that advocate for improved labor conditions in Washington, Seattle, Philadelphia, Houston, LA, Denver and many other cities across the globe.

For more information contact:

* Labor Archives & Research Center, San Francisco State University, 480 Winston Drive, San Francisco, CA 94132 USA. Telephone: 415 564-4010. Fax: 415 564-3606. Email: larc @ sfsu.edu. Internet: http://library.sfsu.edu/larc

* International Federation of Bike Messenger Associations, PO Box 191443, San Francisco, CA 94119-1443 USA. Email: magpie @ messengers.org Internet: http://www.messengers.org/

Nicholas Wright curated and organized the labor organizing materials that are now housed at LARC. He is a former assistant at LARC.

Home | About Us | Contact Us | Contributions | Economics | Education | Encouragement | Engineering | Environment | Bibliography | Essay Contest | Ibike Tours | Library | Links | Site Map | Search

![]()

The International Bicycle Fund is an independent, non-profit organization. Its primary purpose is to promote bicycle transportation. Most IBF projects and activities fall into one of four categories: planning and engineering, safety education, economic development assistance and promoting international understanding. IBF's objective is to create a sustainable, people-friendly environment by creating opportunities of the highest practicable quality for bicycle transportation. IBF is funded by private donation. Contributions are always welcome and are U.S. tax-deductible to the extent allowed by law.

![]()

![]() Please write if you have questions, comment, criticism, praise or

additional information for us, to report bad links, or if you would like to be

added to IBF's mailing list. (Also let us know how you found this site.)

Please write if you have questions, comment, criticism, praise or

additional information for us, to report bad links, or if you would like to be

added to IBF's mailing list. (Also let us know how you found this site.)