|

Ethiopia: Abyssinia Adventure - Hwy 3 Saalalii Plateau Bicycle Africa / Ibike Tours |

|||

|

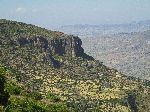

Highway 3 wanders to the north and west across the Ethiopia plateaus, dipping into gorges and crossing mountains. The road passes through spectacular countryside and traverses some of the culturally rich territory of the Amhara, Agaw and Awi Peoples of Abyssinia. Visitors are shown some of the wonderful hospitality of the region. Both the people and the scenery seem to get more and more wonderful every day. |

||

|

Exiting -- some might

say escaping -- Addis Ababa, the road climbs Entoto Hill. The two-lane

road has been widened in many places in the last few years but many sections

are still too narrow to provide much comfort when the adjacent lanes are

filled with vehicles as well. Winding along the face

of the slope and with multiple switchbacks, the road gains more than 400m (1300 ft) of

elevation in about 5 kilometers. Unfortunately, from above the town, what should be an expansive view of Addis Ababa is often obscured by the gray hue of the city's air pollution problem. The immediate environment is much more pleasant because much of Entoto Hill is planted in eucalyptus, creating a substantial forest. |

|

|

|

A

bas relief art installation carved into the rock along side the road

climbing out of the city includes many of the iconic images of the nation; the stone

hewed churches of Lalibela, obelisk of Axum, Lion of Judah, and giraffes. A

bas relief art installation carved into the rock along side the road

climbing out of the city includes many of the iconic images of the nation; the stone

hewed churches of Lalibela, obelisk of Axum, Lion of Judah, and giraffes. |

|

|

|

Along the switchbacks, which are populated by lumber trucks, broken-down

vehicles, donkey traffic hauling goods from villages to the

city and long-distance runners in training,, is a bilingual traffic safety sign counseling drivers to wear their seat

belts and not talk on cell phones. There is some adherence to following the seat

belt laws but many drivers ignore any prohibition against using mobile phones

while driving. Along with all of the motor-traffic on the road, there is an astonishing the number of load-laden donkeys and people streaming into the city on foot. After cresting at 2630m (the first peak on the graph below), the plateau rolls for the next 80 km (50miles), to Debre Tsege, 1000m above the gorges of the Jamma River and Muger River with an average elevation of just over 2630m (8680 feet). Ethiopians tend not to name geological features like this so it doesn't exactly have a name. A term that is applied to the area is Saalalii, but this refers more to the culture and ethnicity, which are not geographically bound. The terms Abyssinia Plateau and Ethiopian Plateau are used for this plateau, but their totality is even broader, incorporating the highlands all around the headwaters of the Nile River and its tributaries in the area.

The plateau's ups and downs are never more than 80m higher or

lower, and if you are acclimatized it is a pretty pleasant ride.

If you are not acclimatized, even if you are in shape for the lowlands, each climb

seems brutal. But, if you rest at the top of the

climbs, take a few deep breaths, stay hydrated and pause for a minute, you rebound pretty well

-- until the next sustained climb when your legs again feel like lead. It is nice of Google to generate these topographical graphs, but they are a little deceptive: On this graph the vertical axis coves 300 meters and the horizontal axis covers 85,000 meters. In reality the steepest slope on this section is not a cliff, but only an 11% grade. The average up slope is 2.9% and the average down slope is 2.2%, so a lot of the ride seems pretty flat.

Some of the chatter in the graph is created because Google route lines don't

always superimpose on the road accurately. So if the route line runs off

the road into a gully and then come back on to the road the computer code that

is analyzing the GPS elevations is going to show a dip and climb that don't exist

on the road, which tends to have steady grades. |

|

|

|

Not long after cresting

the forested south slope of the hill, the modern elements of the capital city

subside and traditional architecture is more common. In this area,

round houses with thatched roofs prevail. The traditional buildings of this

mixed Amhara/Oromo area tend to range from small to medium-size houses without any distinguishing features or

adornment, to much larger buildings with additional architectural features. The

former are typically associated with the Amhara and the latter with the Oromo.

It is this ethnic mix that distinguishes this plateau. Both the Amhara and Oromo

in this area are predominantly Orthodox. |

|

|

|

The challenging switchbacks of Entoto Hill give way to a high plateau with long stretches of straight

roads and gentle grades. While the expansive views are marvelous, the physical activity is deceptively

hard for people accustomed to much lower elevations. The average elevation in this section is 2600m (8500 ft) and the plateau

is regularly etched by a river valley, which after a nice decent of a couple

hundred meters, requires you to climb a couple hundred meters back out again.

This can knock you out, but after a stop for a few deep breaths the body

recovers remarkably. |

|

|

|

The first major town

outside of Addis Ababa is Sulutan (elev. 2600 m). The town center is

marked by a monument of a horseman and bas relief plaques. At a high point at the edge of town is a characteristically round Ethiopian Orthodox church. The Abyssinian highlands are predominantly Ethiopian Orthodox Christian. Every settlement of any size has a church nearby and even a small town might have several churches. Traditionally churches are surrounded by trees, so often, at best, you get a peek-a-boo view of them. The alignment of the road and break in the trees provide a clearer than normal view of the church in Sulutan. Most of the thousands of churches on the route -- even the finest -- don't get immortalized in the photographic record because their features can't be seen well through the camera lens.

As more and more rural highways were paved, about 2010, three-wheeled Bajaj (tuk

tuks) started to appear in rural town around Ethiopia in large numbers. They are

the people taxis of small towns. An indicator that a town was coming is Bajajs

start to appear on the road 5-10 kilometers before the town, and the density

increase as you reach the town. They are surprisingly durable and don't limited

themselves to the pavement. Goods are still mostly transported more

traditionally -- by donkey. |

|

|

|

Besides the road itself,

there are only a few examples of economic development infrastructure along the

road: Relatively low-capacity power lines run down the field paralleling the road. In Sulutan there was a water station with standpipes. Many other similar set-ups seem to be overgrown and abandoned, presumably because something in the system had broken. What do the people who depended on these installations for water do now? Whose responsibility is it to fix the problem? There are

also numerous signs of bilateral development assistance. Cars passed that were associated

with Japanese technical assistance, USAID, German development, for example. The sign (left) is for an Ethiopia-Korea water development project (photo

to the right). |

|

|

|

There are also

signs indicating local agro-industry in the form of dairy (left) --

but no dairy cows are to be seen from the road. There are also

signs indicating local agro-industry in the form of dairy (left) --

but no dairy cows are to be seen from the road.The new agro-industry on the

plateau is horticulture (flowers). Most of these are joint ventures between

Ethiopians and foreign investors. They are criticized for taking land from local

farmers without fair compensation, but the developers argue that they provide

jobs planting and cutting flowers. Of course in this case the job is at someone

else pleasure and if the ex-farmer looses the job they have nothing to eat. |

|

|

|

There is extensive farm

land on the plateau. This is not a district that is usually subject to the

food crisis that have attracted media attention. Given the relatively

sparse population and the flow of goods into Addis Ababa, it would appear that this

region exports food and helps to feed other parts of the country. But like

farmers everywhere, they are subject to the fickleness of the rains -- too

little or too much.

|

|

|

|

There are a few signs of

industrialization on the plateau, most attributable to the Chinese. The

first large installation is a leather factory north of Sulutan. Here the

buildings are large, but the parking lot is empty and there is little activity to

be seen. Maybe the action is seasonal or in some other way periodical. One quirky consequence of Chinese investment is that "China" has become the moniker for all foreigners. Bicycling past them, the kids will yell, "China, China, China!" It is not clear whether they really think we are Chinese. Do all foreigners look alike? Or are they a little vague about what they are saying? Another anomaly in the area is an upscale travelers' rest stop serving fancy coffee, cake and Western food. I view it as an indication that the

middle class Ethiopians are traveling and using this road. |

|

|

|

The next large village or

small town is Chancho (elev. 2,620 m). Houses stretch partially around the base

of the hill and climb up it some, but again, the hill-top position is dominated

by an Orthodox church. The next large village or

small town is Chancho (elev. 2,620 m). Houses stretch partially around the base

of the hill and climb up it some, but again, the hill-top position is dominated

by an Orthodox church.The church at the far right is of the same style but in Debre Tsege. |

|

|

|

A new addition (2015) to the outskirts of Chancho is a cement factory. The wildlife is wonder what will come next. |

|

|

|

Throughout the ride on Highway 3 the vistas beckoned photography. With all the beauty, expansiveness and diversity, there were so many details to remember; color shifts, contrasts in texture, lines and curves and juxtapositions of shapes, and their are ever-changing relationships to one another as we move along. Over and over we stopped and aimed the camera in an effort, sometimes futile, to record and remember and try to answer our numerous questions: To remember the vastness -- always hoping that the next picture would capture it a little better. To remember a gravel road that swept through the foreground and disappeared as its two tracks merged into a single gray line. Where does the road go? What adventures lie ahead if we follow it? To remember a field of hay stacks without a single piece of farm machinery in sight. What would change if mechanical farm equipment was introduced? To remember the prominent crops in an area and the diversity of agriculture. What is the agricultural cycle like here? How do they do crop rotation? To remember a cluster of houses. For how many generations had the family lived there? To remember uniqueness of a cluster of house built closely together or another more spread out. With so much land, what do they consider when locating and building a new house? To remember the layers of hills that peek out from behind one another. Are the local residents as awed by the view as I am? To remember a dedicated farmer, often solitary, working his way up and down the country side hoe-stroke by hoe-stroke. How many times has someone covered every inch of the field on foot? To remember all the other snapshots of life as people worked, played, shopped, prayed and persevered. How does the snapshot inform us about life? And, how is the snapshot deceptive? To remember a family, on foot, journeying across the landscape. Where did they start? What is their destination? To remember a pocket of forest. Was the whole plateau once covered with trees? How did that look? To remember a hillside of terraced farmland. How many generations did it take to rearrange the land? To remember gorges, valleys and canyons. How long does it take people to walk in and out of these chasms? To remember the diversity of architecture in traditional houses. What imaginations created so many variations on a theme? To remember the urban livestock -- how normal the scene is here and how improbable it would be in a western urban setting. To remember the people along the way (although I am reluctant to take these pictures, so they are documented the least.) To remember the richness of rural life. To remember the material culture of Ethiopia. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When the church is close

to the highway there will usually be a collection box at the roadside.

Sometimes the priest himself will be present to bless travelers and actively

solicit contributions.

Muke Turi is a frequent lunch stop. The waitress at the restaurant (right) asked to take our picture with her cell phone. We agreed if it was reciprocated. Now her smile and charm can be enjoyed by everyone who finds this page of a billion on the Internet. Market day in MukeTuri (elev. 2650 m) features such things as grains, vegetables, local pottery, injera cooking stones, and salt. |

|

|

|

To the left is a traditional Ethiopian coffee preparation set-up, though the table is more elaborate than most. |

|

|

| Beyond Debre Tsege (elev

2640 m) the road

crossing the plateau drops to Debre Libanos (elev. 2510m) and then gradually

climbs to 3100m (10,200 feet) before descending to Gohatsion (elev. 2500m, 8200

feet), over the course of 90km (56 miles).

|

|||

|

The

kaleidoscope of scenes continues: The

kaleidoscope of scenes continues:Approaching Debre Libanos the road descends 100m (330 ft), the view opens up, and the earth drops away into the Jemma Gorge. The roadside viewpoint is populated by young, aggressive curio sellers, which

makes it hard to experience and appreciate the vastness of the gorge. |

|

|

|

The

huge Jemma River gorge is breath-taking. It is deep, wide and long. The

huge Jemma River gorge is breath-taking. It is deep, wide and long.On the nearside, the terraced hillsides are impressive and extensive. How did people get to some of these places? Did it take decades or centuries to build all of the earthworks? The final challenge must be extricating the farm goods after the fields are harvested. |

|

|

|

The

dominant craft in Debre Libanos is carved marble. Numerous sellers have their

wares displayed along the roadside. The primary objects are Orthodox crosses,

but there are other items and religious icons as well. The

dominant craft in Debre Libanos is carved marble. Numerous sellers have their

wares displayed along the roadside. The primary objects are Orthodox crosses,

but there are other items and religious icons as well. |

|

|

|

The exhilaration of the descent into Debre Libanos is terminated with a return to reality where it bends around to a new climbs that continues past Fiche (elev. 2800 m) to finally crest at above 3100m. The grade is not at all steep but the elevation kicks you down if you are not acclimatized. |

|

|

|

The largest town on the Saalalii plateau is Fiche. It like everyplace else in

this part of Ethiopia is experiencing a building boom. This picture shows four

multi-story building under constructions. There were twice this number

along a short stretch of the highway also taking form, they just couldn't be

included in the same photo. There are also signs that rural construction is

also robust. These donkeys (right) hauling poles are not unique. |

|

|

|

It

takes a well-timed double take to spot a single income generator in this area. The

milk cows are totally out of sight. But, in the early morning and late afternoon there are a lot of small

milk cans around. It

takes a well-timed double take to spot a single income generator in this area. The

milk cows are totally out of sight. But, in the early morning and late afternoon there are a lot of small

milk cans around.

When the collection truck comes around it all take shape: People come out from behind fences and converge from scattered groups to line up. The quality control tester works his way down the line, amounts are recorded and the very fresh milk is poured into barrels on the truck for transport to the processing plant 150 kms away in Addis Ababa. Someplace not far beyond Fiche seems to be the outer limits of this small-holder activity. Most likely the collection and transport is not economical over longer distances. After the

milk is delivered to the truck, the people with their small cans walk back into

the hills and disappear. |

|

|

|

Past

Dagam (elev. 3080 m), almost hemorrhaging out of the highway and farmland,

there's a

new (2012) cement factory -- an investment by the Chinese. Past

Dagam (elev. 3080 m), almost hemorrhaging out of the highway and farmland,

there's a

new (2012) cement factory -- an investment by the Chinese.Much of the current output of cement is probably destined for the mammoth Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), a ten-year dam construction project on Nile River festooned with great promise for the future. Time will tell if it will live up to its promises. The government of Ethiopia is dismissive about any suggested negative ecological and humanitarian impacts on upstream and downstream inhabitants along the river -- from its source to the delta in the Mediterranean Sea, a distance of 3800 km. In addition to Ethiopian environmentalists, the governments of Sudan and Egypt have expressed concerns. (The three countries signed a new agreement on water rights for the Blue Nile in 2015.) Across the road from the cement factory was a table tennis

game. It is one of two table tennis sets I have seen in Ethiopia -- the other

was a few miles away. My conclusion is it is connect with the Chinese presences. |

|

|

|

The inclined plain that

created a 35km climb east of the crest (3100+m), tilts the other direction to the west of

it. In the first 8km the elevation drops a couple hundred meters to Ali

Doro (elev. 2820 m) and then continues to gently drop 300m for most of the next 75km. The inclined plain that

created a 35km climb east of the crest (3100+m), tilts the other direction to the west of

it. In the first 8km the elevation drops a couple hundred meters to Ali

Doro (elev. 2820 m) and then continues to gently drop 300m for most of the next 75km. |

|

|

|

A whimsical garden in Ali

Doro:. In addition to other elements it has a very unique topiary of what appears

to be two people dancing. As we traveled west, it was more frequent that kids ran along side the bikes and gathered around us when we stopped. The running must reflect the stamina that their lifestyle develops. From there it is not a big step to understand why Ethiopia consistently produces world class marathon runners. The kids are running barefoot on the pavement, creating a flashback to Abebe Bikila's winning performance at the 1960 Olympics. |

|

|

|

Road across Abyssinia Plateau at 2600m. |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Unique Programs To Special Places For Memories Of A Lifetime!

"Hosted by

DreamHost - earth friendly web hosting"

|

|